After growing up in Midland, Susan Swan says the wild freedom she experienced shaped who she is today as she fights for a level playing field for women who write

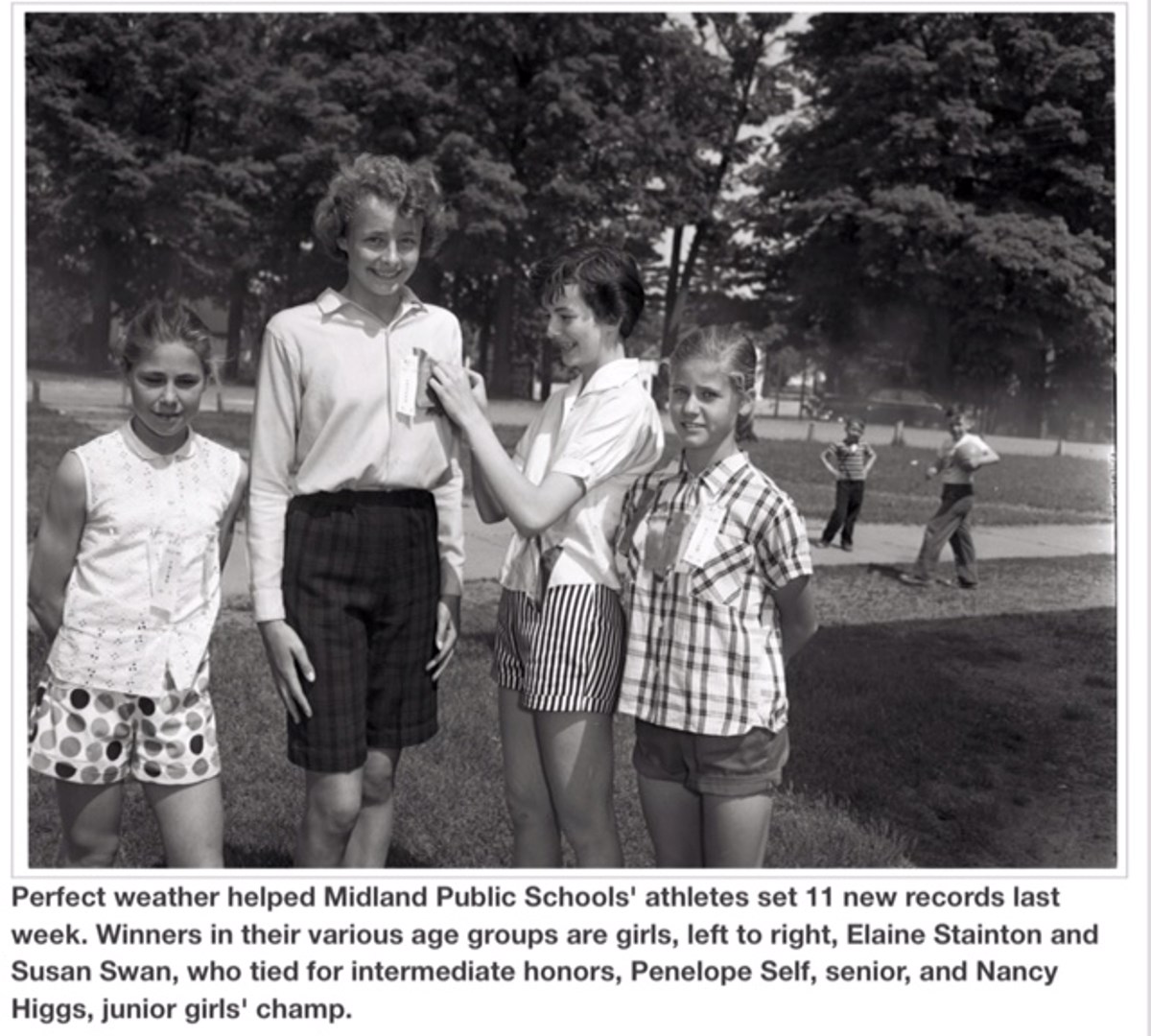

As a former journalist who got her start at the Midland Free Press in the mid-1960s, bestselling author Susan Swan appreciates good reporting.

“It’s very hard to have a democracy if you can’t have newspapers,” Swan said, lamenting the loss of some local newspapers in recent years.

Swan learned an important lesson in fact-checking, accuracy and balanced reporting when she wrote a front-page article in the Midland Free Press about cottagers who may not be able to access their properties in winter.

The article caused a stir and the owner of the Midland Free Press, who was absent when the then-teenage journalist’s article appeared on the front page, returned to explain to Swan how to deliver solid reporting that offers perspective and checks the facts .

The newspaper owner told the rookie reporter that the council could not prevent people from visiting their property.

“He said to me, ‘It’s going to hundreds of people, and they’re going to believe it,'” she recalls.

Swan says she thinks a lot about that statement now, with former US President Donald Trump in such need of constant fact-checking that Daniel Dale, a reporter then working for the Toronto Star, won awards for correcting it. Trump’s constant inaccuracies.

“This kind of journalism is crucial in a democracy,” Swan says, “otherwise any idiot can stand up and say ridiculous things.”

Swan’s literary work is equally rigorously written and edited and he is credited with recreating this Georgian Bay community well and in detail in western light.

Published in 2012, the novel brings to life the experience of Swan growing up in Midland in the 1950s. It recreates Midland in all its quaint, small-town glory as a place of wonder and freedom.

“It’s my tribute to what Midland gave me,” Swan said. “It’s a beautiful landscape to grow up in. We had the freedom to roam that city kids didn’t have back then.

Every detail of the novel has been researched for accuracy because it is historical fiction – until flamingos began appearing on people’s lawns as ornaments in 1957.

The story recounts the author’s own upbringing in a town passionate or obsessed with hockey.

In the 1950s, the mayor of Midland listened to or watched hockey games from the porch in all seasons while his wife called the score.

“She was afraid he was going to have a heart attack,” Swan recalled, stifling a chuckle. “Canadians are a culture that loves hockey.”

Swan recalls a story from her youth that entered the book when she and her mother saw a man climb the fence behind the goalie’s net during a Toronto Maple Leafs game against the Toronto Canadiens. Montreal to challenge a referee’s appeal.

“My mom was like, ‘Oh my god! It’s doc,'” Swan says, noting that’s what her mom called her dad.

western light is a prequel to Swan’s bestselling 1993 novel The Brides of Bath which tells the story of women who came of age in a Toronto private school in the 1960s.

Swan is the author of eight novels including his latest The Dead Celebrities Club written in 2019.

As a retired professor, Swan remains involved with graduate students pursuing writing careers and was recently commissioned to help establish the Carol Shields Prize for Fiction open to Canadian and American authors.

“It all started as an attempt to have a more level playing field,” says Swan.

Swan sat on a panel examining women’s writing over 40 years. After doing some research, she discovered that only a third of literary prizes go to women in Canada and the United States, and that women writers earn only 55% of what men earn.

Of the 119 winners of the Nobel Prize for Literature, 17 are women, including this year’s winner, Annie Ernaux. This prize has been awarded since 1895. Since 1918, only 31 of the 93 Pulitzer Prizes for fiction have been awarded to female authors.

From a strictly Canadian point of view, for the Stephen Leacock Prize for Humor, awarded since 1947, only 10 of the 74 winners are women.

The Governor General’s Award in English has been awarded to women 30 out of 83 times since 1936. The same award began being distributed for French literature in 1959 and has been awarded to women 34 times out of 74.

Women are starting to win more literary awards now.

The Scotiabank Giller Prize for Fiction is a prime example of a fairer opportunity and has been awarded to female authors 13 out of 28 times since 1994.

When everyone at the Vancouver panel was amazed by these statistics, a group of female authors came together to raise approximately $3 million for the creation of the Carol Shields Prize for Fiction.

There are 11 mentorship programs with various organizations and universities that offer grants and residencies to emerging female authors.

What afflicts Swan most is that women write as much as men, but because the highest level of critics are often male, when they consider the best authors of the last 30 years, they tend to name men.

They often view women’s writing as ordinary, irrelevant, or about domestic matters.

“That’s the good thing about Carol. That’s what she wrote. The life of women in the domestic sphere. She wrote about the invisibility of women’s lives with radical banality.

In a slice of nothing ordinary, Swan’s next book will be a memoir about growing up as a taller woman in the 1960s, titled Too big.

“I was told I was too fat to be feminine, because I’m 6’2,” Swan explains.

Expect these memoirs to be released in the near future.

If you can create art from Canada’s love of hockey through literature and hold the literary world to account on behalf of women, what could be more feminine and radically ordinary than that.

“Internet evangelist. Extreme communicator. Subtly charming alcohol aficionado. Typical tv geek.”