The sounds do not speak for themselves. But neither are the images. Much less words. The enormous amount of information it takes to understand even the simplest word, say water, is almost immeasurable. You have to know a world to understand a word. Or maybe not so much. But it is very complex. And if we move from regulated domains, like those of language, to more volatile ones, like image or sound, the question seems more complex. In fact, until Raymond Murray Schafer, who died on August 14 at the age of 88, no solid analysis had been done in such detail. There were already sound psychologies in the twenties; treated with acoustics, centuries ago. However, no one had ever tried to understand the relative autonomy of sound within the world that generates it.

Soundscape and acoustic ecology

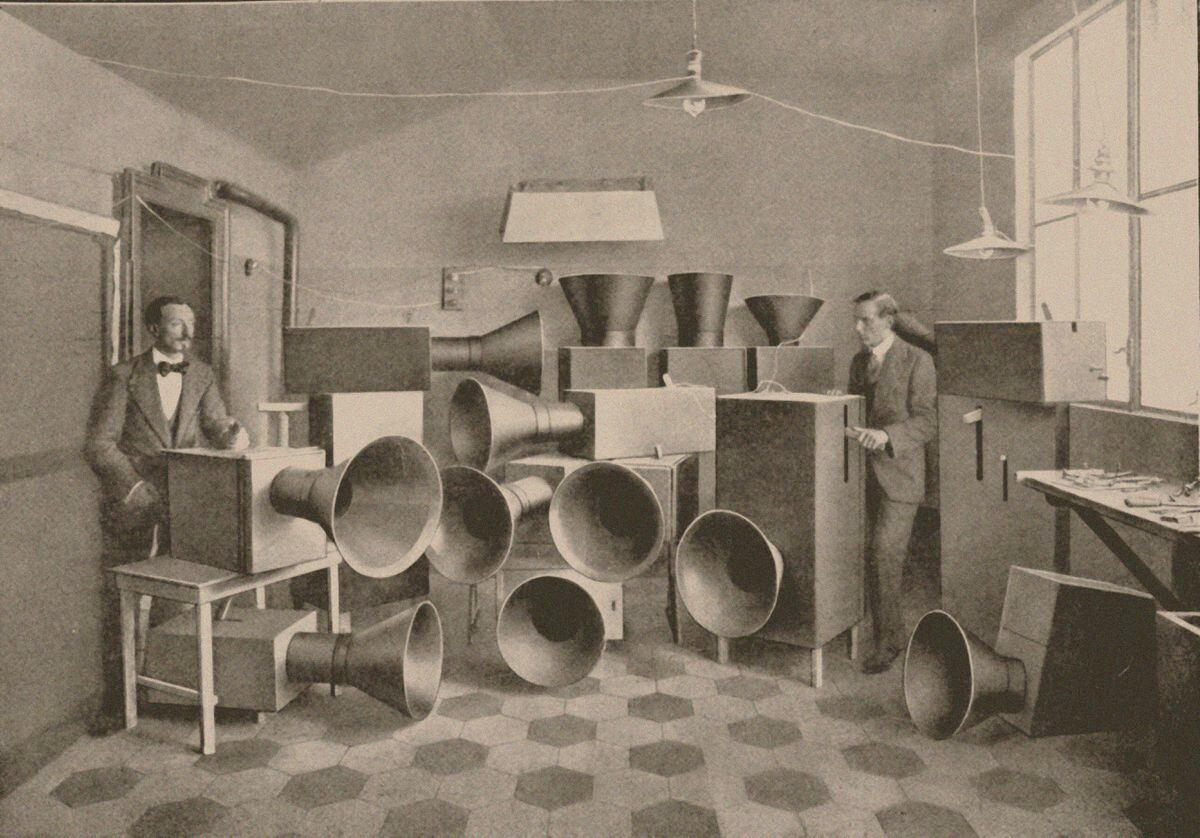

Raymond Murray Schafer was a great creator of a now standardized terminology: soundscape, clairaudience, acoustic design, schizophony, ultrasound, sound mark or acoustic ecology. And although he is especially recognized by the first concept, which gives his name to his most systematic book, The soundscape (1977), his obsession revolved around the latter. Indeed, the driving force behind Murray Schafer’s work was the fatal impact that the changes in the soundscape of the past three hundred years have had on the population. The origin of the problem, for the author, was the industrial revolution. This has led the world to levels of noise pollution that it considers unsustainable. He filtered his express activism through important educational work. And his proposal was clear: to take a step back, to return to a solidly sustainable environment. A reactive gesture, which Income in the countryside – perhaps miserable, but noble – after having tried his luck in the city – inhuman and Cainite – which represents so well the Phalangist brochure edited by Nieves Condé, Grooves.

Schafer was a great creator of now standardized terminology: soundscape, “clairaudience”, acoustic design, “schizophony”, “ultrasound”, “sound mark” or acoustic ecology

Despite all the complexity of the concepts he weaves, the Canadian’s proposals had no other effective purpose than to serve as an appeal to the powerful to legislate on noise (another of his main subjects of interest). Outside his framework of analysis was the fact that this noise which frightened him was the effect of an economic mode of production which generated social conflicts which have no turning back and for the resolution of which legislation , whatever it is, is, of course, unnecessary. This is the limit of any theory that wants to represent sound as an autonomous entity. Because, if Murray Schafer’s analyzes are unprecedented, the demand for an acoustic ecology is an ideology that is now more than a century old.

One of the current researchers of sound studies, Samuel Llano, uses in his book Discordant Notes (recently translated into Spanish) of a neologism very close to that of acoustic ecology: that of hearing hygiene, which serves as a guide to understanding a legislative practice on noise that the self-proclaimed middle class – that is to say – say the emerging petty bourgeoisie of the late nineteenth century XIX – used in its process of social legitimation against the working class; a case of practical application of the idea of “social hygiene”, with all the meaning given to the term by the Lombroso and Nordau or, here in Spain (the area studied by Llano), Salillas or Bernaldo de Quirós.

Solid social history

At another theoretical point, almost antagonistic, is the recently deceased Ian Rawes who, after a “short illness”, died on October 19 at the age of 56. His relationship to sound was very different. I was in charge of the project The London Sound Survey, the largest archive of field records that has been generated on any city. Rawes, although in recent years he was already very reluctant to theoretical practice (“At first he wrote pompous texts on documenting the sounds of the city, as if he was doing people a favor …”) and his obsession was only As an archivist he coined the term sound social history for his work. His basic intuition was that useful information is preserved in sounds that are lost in other sources. If Murray Schafer literally audited Vancouver and compared it to the French countryside to show how unbearable the city was, Rawes questioned the reasons for the acoustic differences between a suburb and a residential area in the City of London. Plus, Rawes didn’t use the pitch as a sobering example. Derek Walmsley recuerda que, hacia 2019, Rawes tenía en mente utilizar sus técnicas de registro sonoro para representar las mutaciones que experimentaban los trabajadores de una zona interior de Cambridge a caballo entre el rural y las zonas industrializadas con el cambio en las dinámicas de explotación de land. Sounds, for Rawes, were able to reconstruct parts of social relations that the image or the word let slip.

Rawes was in charge of The London Sound Survey project, the largest archive of field recordings that has been generated over any city

His interest in sound recording also led him to build up an impressive sound history of London. His archives consisted of several tens of thousands of non-musical sound recordings, including field recordings made by him and historical recordings compiled by him. Even though he was clear about the recording’s function as a source for historians – and, in fact, one of his main obsessions in recent years has been finding a way to preserve a digital archive, an example of obsolescence. par excellence – he sometimes let himself be carried away by pleasure, artizaba the archive, ceased to be an archivist to become a collector, showing a certain fetishism (understandable when one leads a life between records). In fact, his work is valued much more in the field of musical experimentation than in that of social history. The methodology is still to be developed and, for the great majority of historians, sound recording is a source, for the moment, unintelligible. The codes are missing. Because it is a sham to let the sounds speak. Because sounds, like words, do not speak, but encrypt relationships and situations; relationships and situations that deserve to be understood. Raymond Murray Schafer and Ian Rawes have dedicated their lives to this thankless task. In the same area. At opposite poles.

You can follow BABELIA in Facebook and Twitter, or subscribe here to receive our weekly newsletter.

“Evil alcohol lover. Twitter junkie. Future teen idol. Reader. Food aficionado. Introvert. Coffee evangelist. Typical bacon enthusiast.”